If you’ve studied piano for a little while, chances are you’ve bumped into the word sonatina—often right before meeting Clementi, Kuhlau, or Diabelli. But what is a sonatina, exactly, and why do teachers love them so much?

Quick Definition

A sonatina is, literally, a “little sonata.” In practice, it’s a shorter, lighter work—usually in two or three movements—whose first movement follows a simplified sonata form (clear exposition and recapitulation, with a very short development or none at all). Because of their clarity and manageable technique, many sonatinas live in the student repertoire, though not all are easy.

Where Did Sonatinas Come From?

- Baroque roots. The term shows up as early as the late Baroque. J. S. Bach labeled some short orchestral introductions to cantatas “Sonatina,” and G. F. Handel wrote one-movement keyboard sonatinas, compact harpsichord pieces that already hint at the “miniature” idea.

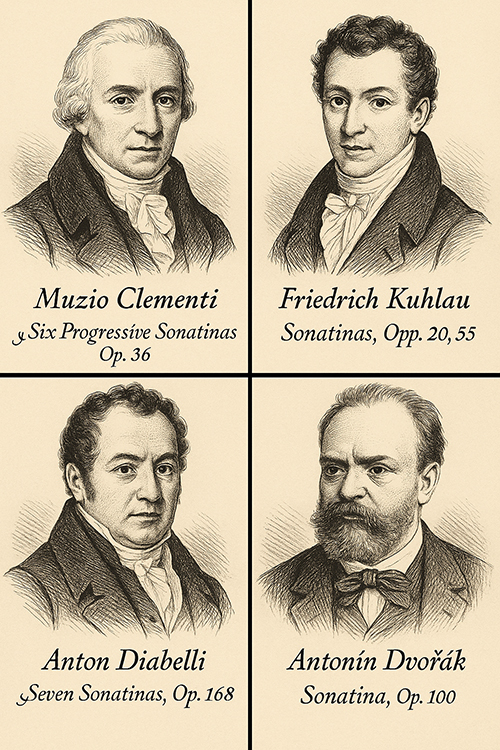

- Classical classroom. In the Classical era the genre blossomed as teaching music. The most famous example is Muzio Clementi’s Six Progressive Sonatinas, Op. 36 (1797)—explicitly graded for learners and still a rite of passage for pianists today.

- Not just for solo piano. While the word is most common on keyboard pieces, composers also used it for chamber works (for example, Dvořák’s Sonatina for violin and piano).

What Makes It a “Sonatina” (Musically)?

Think of the first movement as sonata-form in miniature:

- Exposition: a primary theme in the home key, a transition, and a contrasting theme in a closely related key.

- (Little) Development: sometimes just a short modulatory bridge—or it may be skipped entirely.

- Recapitulation: the themes return, now both in the home key, and we wrap up quickly.

Later movements are flexible. Many sonatinas have two movements (fast–slow or slow–fast) while others have three: fast (sonata form), slow (often song-form or theme-and-variations), and a lively finale (frequently a rondo).

On the keyboard, expect transparent textures—Alberti-bass patterns, clear melodies, scale runs, and tidy phrases—which make musical structure easy to hear (and to teach!).

Sonatina vs. Sonata

“Sonatina” is a label, not a rigid rulebook. Many sonatinas are shorter, lighter, and technically simpler than sonatas—but some composers use the word for serious concert works (see Ravel below). Conversely, some pieces titled “sonata” are easy enough that they could’ve been called sonatinas (e.g., Beethoven Op. 49 are “Two Easy Sonatas”). In other words, the title reflects the composer’s intent more than a fixed difficulty level.

Famous Sonatinas You’ll Actually Meet (and What to Listen For)

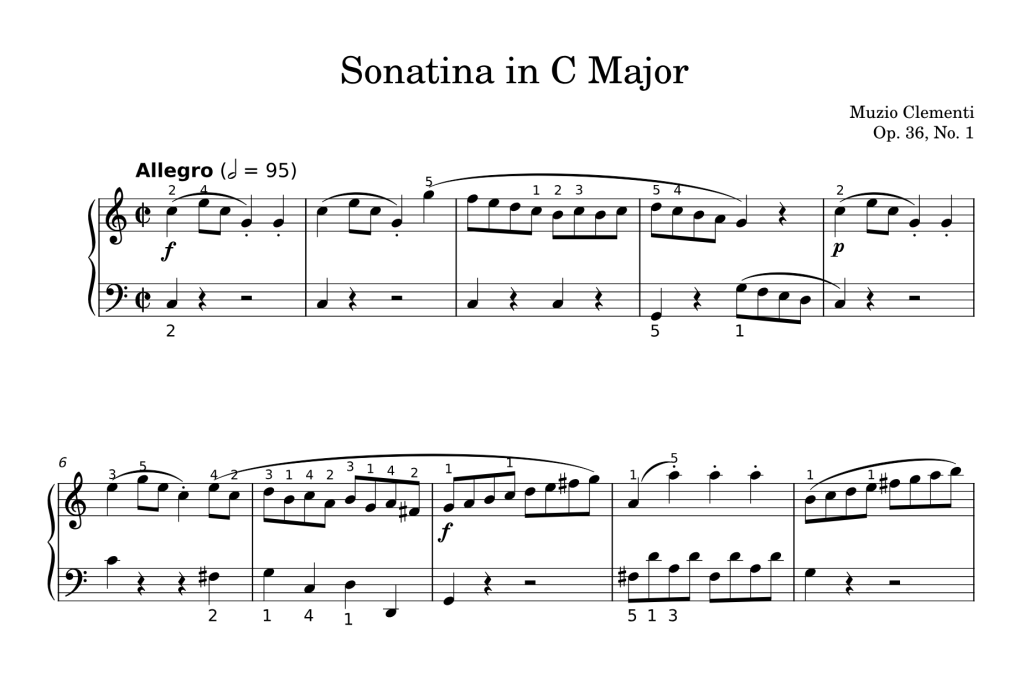

1) Muzio Clementi — Six Progressive Sonatinas, Op. 36 (1797)

The cornerstone set. Clementi designed these as a graded path: simple textures, elegant melodies, and a crystal-clear take on Classical form. Perfect for learning how exposition → (mini) development → recapitulation works at the keyboard.

Among these six, the Sonatina in C major, Op. 36 No. 1 is by far the most famous. It is frequently chosen for recitals, exams, and early Classical repertoire study, making it the quintessential “first sonatina” for many pianists.

2) Friedrich Kuhlau — Sonatinas (Opp. 20, 55; 1820s)

Kuhlau’s sonatinas are often called “sonata form in miniature.” They balance lyrical themes with scales, arpeggios, and occasional left-hand octaves—great stepping stones toward Haydn/Mozart/Beethoven sonatas. A classic starter is Op. 55 No. 1 in C major (1823).

3) Anton Diabelli — Seven Sonatinas, Op. 168

Also staples for students and festivals. Diabelli—himself a teacher and publisher—aimed these straight at the teaching studio: charming, compact, and idiomatic for smaller hands.

4) “Beethoven” Sonatinas in G and F (Anh. 5) — attribution doubtful

You will find these in anthologies and syllabi, but most scholars today doubt Beethoven’s authorship. They’re still lovely, approachable pieces—just don’t treat them as core Beethoven.

5) 20th-Century (Not-So-Easy) Sonatinas

- Maurice Ravel — Sonatine (1905): a refined three-movement work, deceptively slim yet technically and musically demanding; the neoclassical title nods to earlier French keyboard style.

- Béla Bartók — Sonatina, Sz. 55 (1915): based on Romanian folk tunes; short movements, but rhythmically and stylistically rich—more recital piece than exercise.

Why Pianists (and Teachers) Love Sonatinas

- They teach form. You can see and hear sonata principles without the length and complexity of a full sonata.

- They build classical technique. Clear right-hand melodies, Alberti-bass patterns, scales, and light articulation make them ideal for developing evenness, balance, and stylistic pedaling.

- They’re motivating. The music is tuneful and recital-friendly; learners feel like they’re playing “real Classical repertoire” (because they are).

Typical Movement Layout (With Listening Tips)

- Allegro (sonatina form).

- Hear the two themes: a bold opening idea, then a smoother second theme after a short transition.

- Watch for the tiny development: a few measures that sequence or modulate briefly.

- Spot the recap: both themes return in the home key, often with small changes (and fewer fireworks).

- Slow movement (Andante/Adagio).

- Often song-like; singable melody, simple accompaniment.

- Finale (Allegretto/Presto).

- Often a rondo (recurring refrain) or theme & variations—energetic, witty, and concise.

Great “First Sonatinas” to Learn

- Clementi — Op. 36 No. 1 (C major). Compact, joyful, and pedagogically perfect.

- Kuhlau — Op. 55 No. 1 (C major). Slightly bigger gestures; crystal-clear phrase shapes.

- Diabelli — Op. 168 No. 1 (F major) or No. 2 (G major). Singable and friendly to smaller hands.

Tip: If you want to hear the form, follow along with a score while listening. IMSLP public-domain editions are a great resource.

Advanced Sonatinas (For Your Playlist Later)

- Ravel — Sonatine (three movements; French neoclassical flair; a real recital piece).

- Bartók — Sonatina (folk-tune DNA; rhythm and color front and center).

How “Sonatina Form” Fits Inside the Bigger Sonata Picture

Music-theory books sometimes use “sonatina form” to mean sonata form without a substantial development—essentially exposition → short bridge → recapitulation. That’s why sonatinas are so useful in early analysis: they foreground the bones of Classical form while keeping the proportions friendly (MusicTheory.net).

[IMAGE HERE] Prompt: “Diagram overlay of a sonatina first movement structure, showing exposition (themes labeled A and B), short development, and recap.” [/IMAGE HERE]

Bottom Line

What is a sonatina? It’s a compact, often student-friendly cousin of the sonata—usually in 2–3 movements—with a first movement that distills sonata form to its essence. Learn a few and you’ll sharpen your Classical style, internalize musical architecture, and prepare your hands (and ears) for the big sonatas waiting just ahead.

Leave a Reply